Is Alzheimer’s Hereditary?

Is Alzheimer’s Disease Hereditary?

Anyone who has a mother, father or another direct relative who has lived with Alzheimer’s has wondered if they will get it too. Perhaps you’ve had several relatives diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Perhaps only one side of your family has a history of Alzheimer’s.

How will all of this affect you?

Is Alzheimer’s hereditary?

The short answer is yes and no.

Certain genetic variants can put you at higher risk for Alzheimer’s. Other genetic mutations make someone likely to develop early-onset Alzheimer’s (Alzheimer’s that appears anywhere from age 30 to 60).

But just because you have a genetic variant that increases your risk for Alzheimer’s does not mean you will get Alzheimer’s. Other factors like your environment and lifestyle also play a role in determining whether or not someone will develop Alzheimer’s. For the sake of this article, we will focus on the genetic factors at play.

What are genes?

First, it’s helpful to understand what genes actually are, and why they can determine or have an impact on whether or not someone will develop Alzheimer’s disease.

The human body is made up of cells. Each cell contains deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). DNA tells your cells what to do in order to function properly. Your DNA is found in something called chromosomes. Each chromosome contains thousands of genes. You get these genes from your parents. Genes determine what you will look like, and they can determine your health, what diseases you are presupposed to and which ones you are not.

Sometimes these genes can change. These changes are known as mutations or variants. Mutations can cause certain diseases and are often referred to as deterministic genes. Variants can increase or decrease someone’s risk for a certain disease, but variants do not cause disease. These are often referred to as risk genes.

Certain genetic mutations and genetic variants have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

Risk genes for Alzheimer’s disease

A gene variant known as APOE-e4 is the most common variant connected to an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease. About 25% of the population carries a copy of APOE-e4, which is a variant of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene found on chromosome 19.

This risk gene has been linked to early-onset Alzheimer’s as well as late-onset Alzheimer’s, which is the most common type of Alzheimer’s.

Having the APOE-e4 variant does not mean you will develop Alzheimer’s disease; it just means you are at higher risk than someone who does not carry this variant. Having two copies of APOE-e4 further increases this risk. Only 2-3% of the population carries two copies of APOE-e4.

Other common variants of APOE include APOE-e2 and APOE-e3. APOE-e2 is extremely rare but could help protect against Alzheimer’s. APOE-e3 is the most common variant and has a neutral impact on whether or not someone develops the disease.

Deterministic genes for Alzheimer’s disease

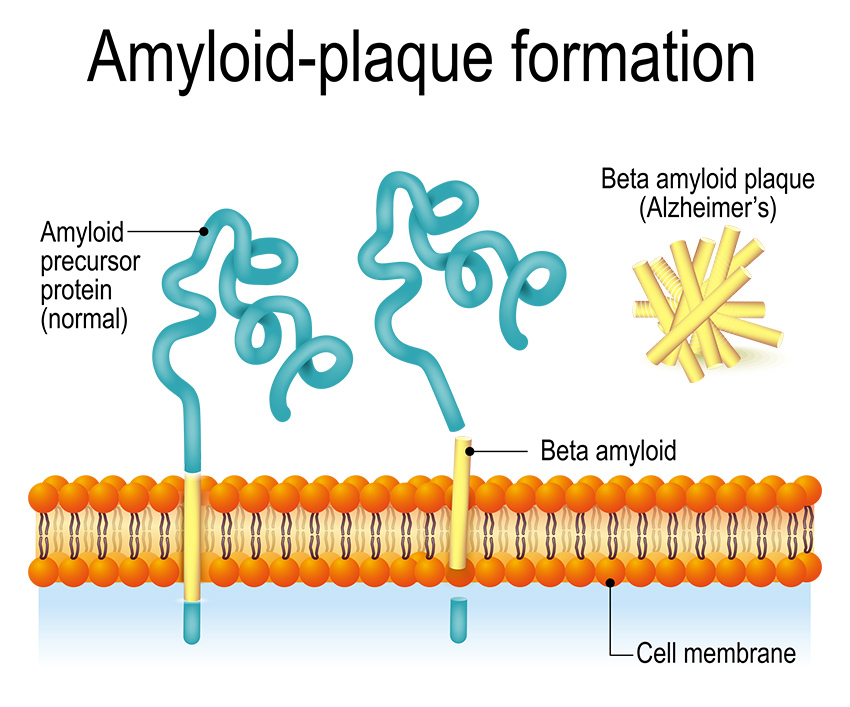

Three known gene mutations can cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: amyloid precursor protein (APP) on chromosome 21, Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) on chromosome 14 and Presenilin 2 (PSEN2) on chromosome 1.

All of these mutations break down APP, a protein that plays an important role in Alzheimer’s. This breakdown can generate harmful forms of amyloid plaques that greatly hinder the function of brain cells.

Someone who inherits one of these mutations from a parent has a strong chance of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s.

People with Down syndrome also have a greater likelihood of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s because their extra copy of chromosome 21 carries the APP gene.

Even though these mutations can almost guarantee a carrier will develop early-onset Alzheimer’s, evidence suggests that if someone carries one of these mutations in addition to a variant that protects against Alzheimer’s, such as the APOE-e3ch, symptoms can be delayed. Knowing this is incredibly helpful for researchers who are developing therapies and treatments for Alzheimer’s.

Genetic testing

Fortunately, with medical advancements, these variants and mutations can be detected through blood tests known as genetic testing. However, genetic testing should be seriously considered first. If you have a direct relative who has lived with early- or late-onset Alzheimer’s, it’s understandable you would want to get tested. But medical professionals highly recommend doing genetic counseling before and after genetic testing to make sure you’re prepared for your results and how to make decisions for your future.

Genetic counselors are not doctors, but they are highly trained in medical genetics and discussing test results with patients. They can talk to you about what your test results mean for your health, your future and your family, and they can help determine if anyone else in your family should receive genetic testing. You can find a genetic counselor near you here.

Because genetic counseling is recommended before doing genetic testing, at-home genetic testing with testing kits like 23andMe are not recommended for testing for Alzheimer’s variants and mutations.

Medication and the future of Alzheimer’s research

Because of genetic testing, Alzheimer’s research has been able to make progress in treatments, medication and therapies. The drug aducanumab (Aduhelm™) is the first FDA-approved therapy that reduces beta amyloids—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. This therapy is not a cure for Alzheimer’s, but it does provide hope that as researchers continue to understand the genetic effects on Alzheimer’s disease, treatment and medication will continue to develop as well.

(If you are a carrier of APOE-e4, taking aducanumab could result in serious side effects. This is an instance when genetic testing is incredibly helpful for those who have already been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.)

If you are considering getting tested for an Alzheimer’s variant or mutation, talk to your doctor. He or she will probably refer you to someone who can determine if you’re a good candidate for genetic testing and someone who could help you find a genetic counselor.

Just because you’re a carrier of a genetic variant or mutation does not mean you will get Alzheimer’s. Other factors are at play. Talk to your doctor or a genetic counselor to make sure you understand the full picture of Alzheimer’s and the impact of your specific genes.